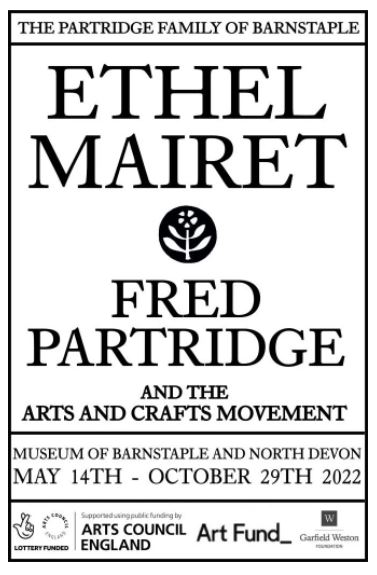

New Exhibition

Exhibition at the Museum of Barnstaple and North Devon. May 14, 2022 – Oct 29, 2022

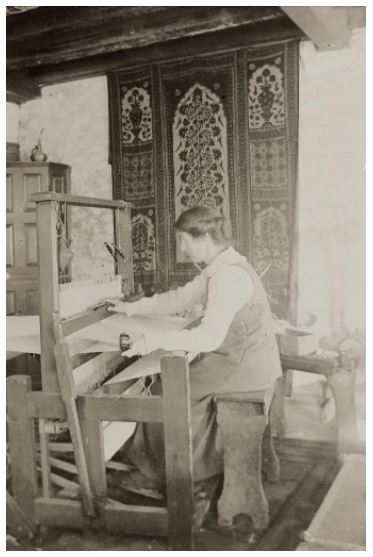

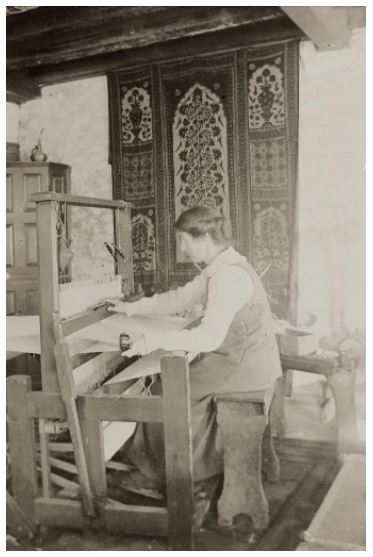

The mother of English handweaving. This is how Ethel Mairet (1872 – 1952) was described by esteemed Japanese master potter Shoji Hamada. She was a highly skilled weaver and pioneer of Britain’s twentieth-century modern craft revival. She was also the first woman Royal Designer for Industry (RDI) in 1939.

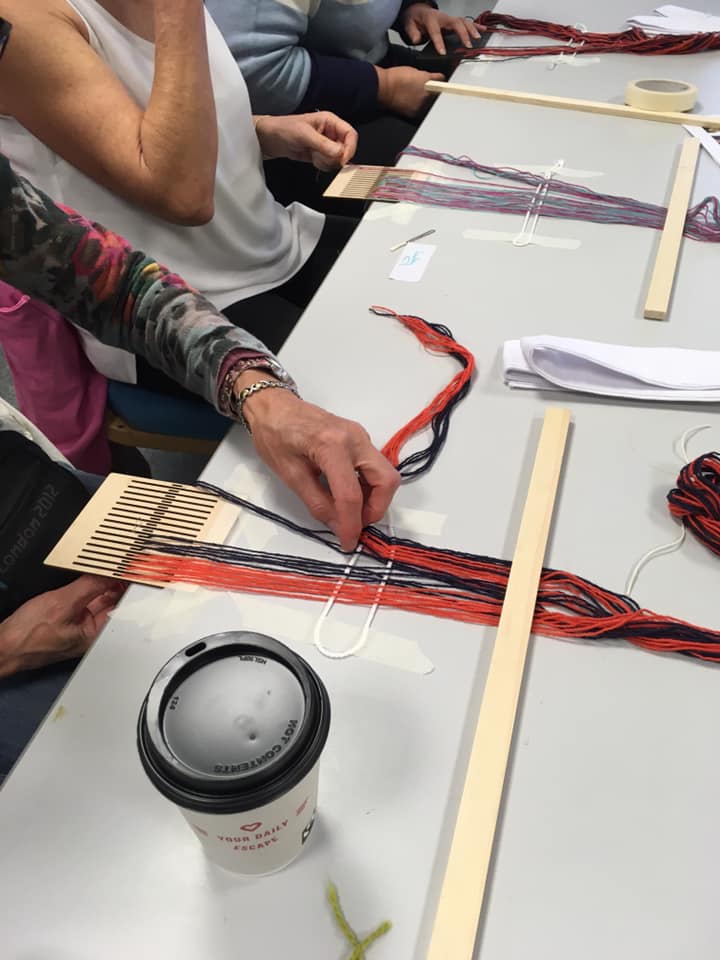

Schools workshop

I was thrilled when I was approached to lead the school’s weave and natural dyeing workshops for Barnstaple Museums’ new exhibition on Mairet and the Arts and Crafts Movement, and I’ve found researching her life’s work fascinating.

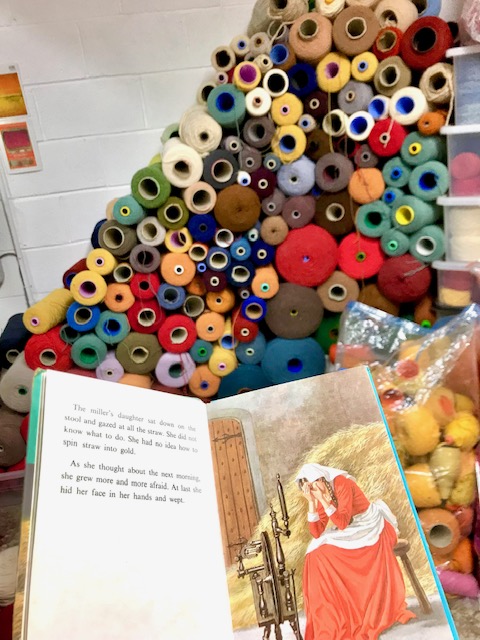

From the onset, I felt a close affinity with Mairet. She was born exactly 100 years before me, spent time living and traveling in India, (as I did in 2006), prioritised colour and combining different textures of yarn in her weaving more than the techniques, (whilst being highly skilled technically), and she taught and influenced Peter Collingwood*, (who’s workshop contents I have recently acquired). The more I discover, the more I want to know and we share a similar approach in our weaving and teaching.

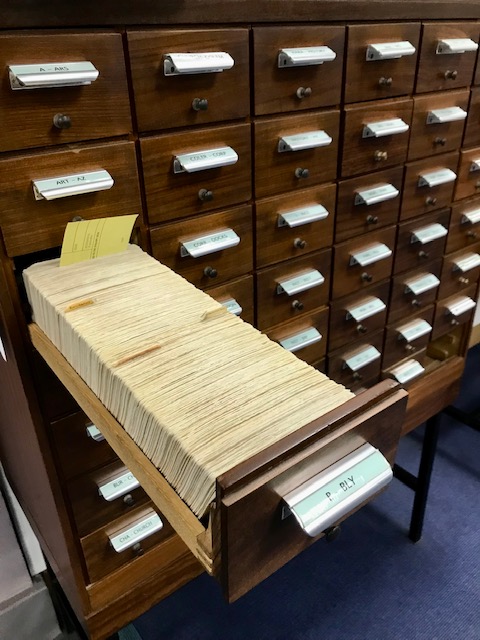

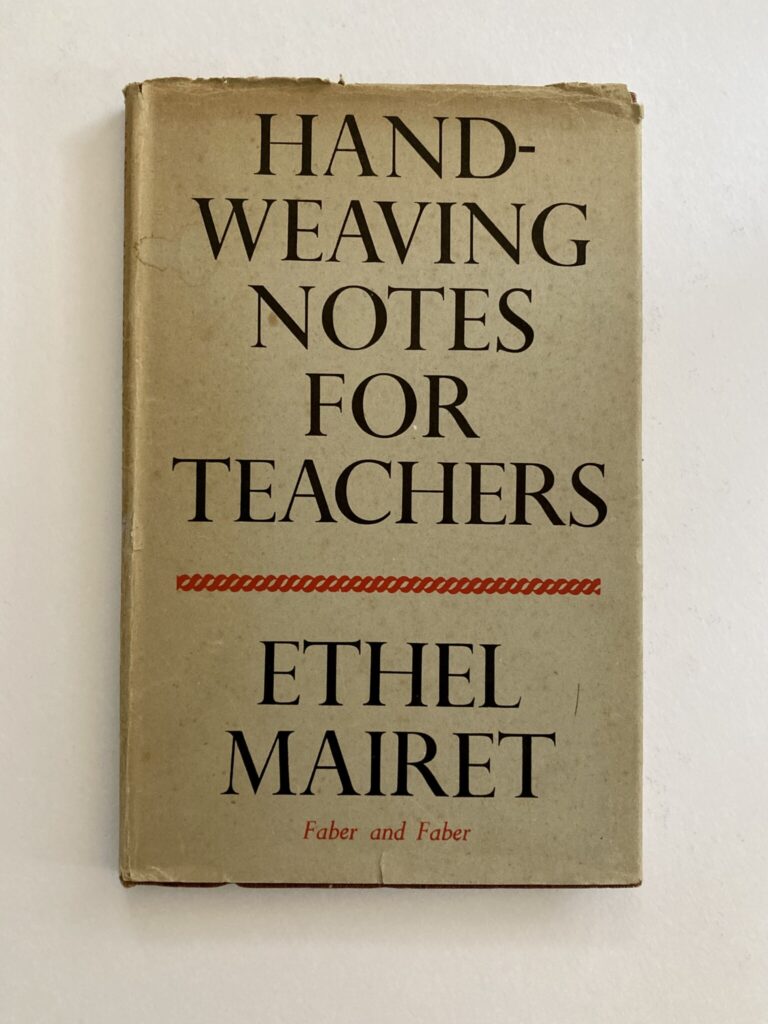

A copy of her rare book, Hand-Weaving Notes For Teachers, serendipitously came into my life when the conversations with the museum first started. This has been instrumental in how I’ve designed the school’s workshops as well as giving me insight into her mindset.

Importance of weaving in schools

In this book, she doesn’t hold back on the impact of the industrial revolution on handweaving and the value of promoting it in schools. Whilst she recognised the economic importance of power looms, she was rightly concerned that without the understanding of materials and design that come through handweaving, the textile industry was taking risks with quality and creating less desirable cloth. These concerns are just as valid 100 years on, as we address mass production, over-consumption, fast fashion, and the impact of this on the climate. In support of this viewpoint, I actively promote the ideology of fewer, better things in my own practice and teaching.

She highlighted the ways in which studying dyeing and weaving connect to other parts of the school curriculum, covering maths, chemistry, and history, as well as design.

This is also still relevant today, and it’s worth mentioning a few additions. I think craft, and particularly weaving is good for the well-being of our young people. The session focuses on the basic weave structures of plain weave and twill, with more emphasis on creating textures through the yarns we will naturally dye in the first workshop. By its very nature, the process will enable the students to be in the moment and find their own rhythm. A practice advocated by those working in the mental health sector. You can read more about the positive impact of craft on your mental health in the article from the Crafts Council https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/stories/4-reasons-craft-good-your-mental-health

I will be using dressed 4 shaft table looms in the sessions, which will give the students an opportunity to gain a greater understanding of the principles of weaving without overwhelming them with the technicalities of warping up.

Sustainable making

Mairet was adamant that teaching in schools shouldn’t be about creating useless and unwanted things, and I entirely support this view. In response, I have created a workshop where the dyed yarns and woven cloth is made up into simple cushions which will be used to create a warm and comfortable space in a communal area. Ideally where the pastoral care team is based. I hope the students will feel a sense of pride in their creations and a better understanding of the value of handmade.

Indian connection

In her notes for teachers, Mairet emphasises the importance of schools having access to “a collection of good, interesting modern and traditional textiles from all over the world, both hand and machine woven as an inspiration for fine workmanship, to help with new ideas”, and to maintain standards of quality.

Like Mairet, I spent time living in India and will be able to draw on this experience in the classroom as well as having examples of textiles collected on my travels to share. (Admittedly these focus more on stitch than weave).

Design

I was pleased to discover that Mairet, like myself, preferred to design at the loom, and saw transferring the pattern to paper as the last part of designing, not the starting point. The paper designs are for reference only. I will encourage the students to simply play with colour and texture when incorporating their naturally dyed yarns into their weaving. I’ll bring along some other interesting yarns to encourage experimentation too.

As an aside, I was intrigued to see that Mairet regarded the teaching of Scandinavian patterns as a bad influence in schools, and in another of her books, she raises concerns that in trying the preserve traditional techniques the creative spirit is killed. She did recognise the instances of imaginative weavers fighting against this trend. Given that I’ve spent almost 30 years trying to exhaust the possibilities of Krokbragd, I would love to have been able to chat to her about this freedom to play with design when using these weft-faced weaving techniques, though I agree that it’s not an ideal starting point from which to learn about weaving in schools.

Materials

Another thing I admire in her work is her receptiveness to the new synthetic materials that were coming onto the market such as rayon and cellophane and the considered way she introduced them into her weaving. I share this interest in using less conventional yarns such as glitter yarns and chenilles alongside wool and cotton in my rugs and woven panels, though I will be looking at sustainable fibre options in the future for obvious reasons.

The more I learn about the significance of Ethel Mairet, the more I would love to have crossed paths with her in life. But given that she passed away 20 years before I arrived on planet earth I have to be thankful that she left behind a series of books, records, and samples. It must have been amazing to experiment in her workshop. Whilst she is regarded as the mother of English handweaving, I quite like the idea of being a mischievous granddaughter, and because of her, I’m delighted to have the chance to share my passion for weaving with the students from Park School.

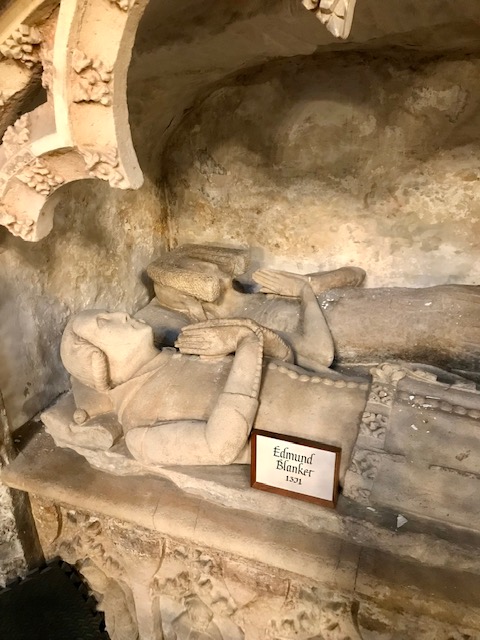

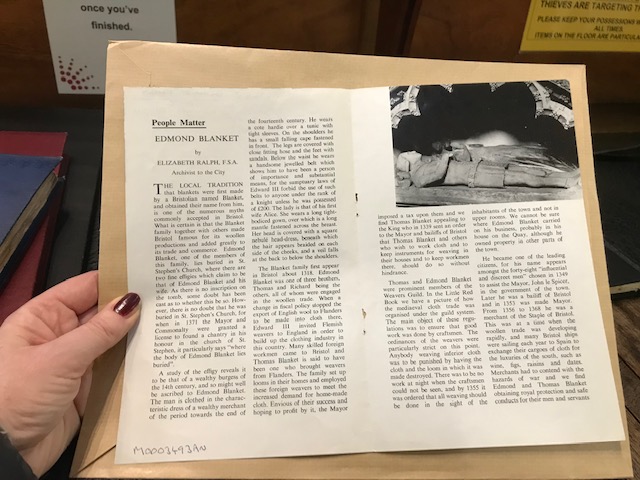

This celebration of her life’s work and teaching at Barnstaple museum is a great opportunity for weave enthusiasts to learn more about her. The exhibition brings together items from the Museum’s own Partridge Geology Collection with loans from national and regional museums including examples of Ethel’s celebrated handmade textiles from the Crafts Study Centre and Ditchling Museum of Arts and Craft; jewelry created by Fred from the V&A, Fitzwilliam and Birmingham Museums; and a first edition copy of a book on Mediaeval Sinhalese art from the British Library.

Book onto a backstrap weave workshop

As part of the exhibition, I will also be teaching backstrap loom weaving during the weekend of activities. Booking details here.

Threading a backstrap loom

A woven sample by a previous student. Similar palette to that favoured by Ethel Mairet

Finishing a woven sample

*In Peter Collingwoods Obituary in the Guardian Oct 25, 2008, Roger Hardwick writes:

On his return to Britain, (Peter) spent six months at Ditchling, East Sussex, in the workshop of Ethel Mairet, then the best-known weaver in Britain. He thought that she accepted him as a pupil because she was intrigued that a man wanted to weave.”

Thanks to Ria Burns and Tom of Holland. For further reading, I recommend Tom’s 2016 blog post on the Mairet collection at the Ditchling museum.

About the author

Angie Parker is a weaver, designer, and colourist. She trained in rug weaving in the 1990s and started her textile practice in 2014. She hand weaves rugs and art panels in her Bristol studio and some of her designs are produced in small batches through various partnerships. She also teaches when her schedule allows. She is currently buried underneath 2 tonnes of rug wool. Sign up to her newsletter here, for updates once she emerges.